Recently, one of my friends of a different race and generation posted a question on social media asking, “What’s a Karen?” He received good responses, mostly copied and pasted from google. I think the tidiest definition for me was:

A Karen is a white woman who feels entitled enough to weaponize her skin color particularly against black men.

Feeling cheeky, I added my own definition, writing, “my face, less woke.”

Seeing my extra pale skin in the little photo next to the comment I sighed – it’s sad, but true.

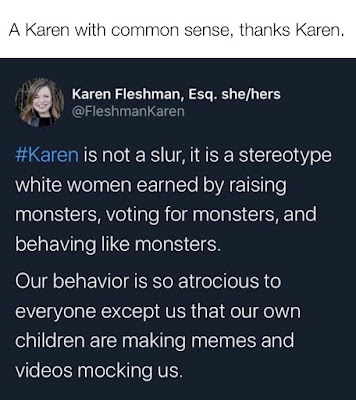

Despite knowing several perfectly wonderful women named Karen, the stereotyped “Karen” as a racist icon has become the meme du jour. They are the wives of Chad, the mothers of Brad and the best friend to Brenda and Becky. All of these people are dangerous but Karen is basically the matriarch of the pro-white movement, so I don’t mind letting her take the fall for the whole lot.

I was born of white women. Raised by white women. Surrounded almost exclusively by white women. Some turned out to be Karens, others not. Now, having lived a third of my life in Africa, where the white women I interact with are actually one in a million, Karen has its own meaning for me. Here, Karen isn’t going to call 911 for feeling threatened by a black man in a hoodie, but colonialist Karen and white-savior Karen have their own ways of oozing superiority. All that to say, my minority status here doesn’t give me a pass. There’s not a single white woman on the planet who doesn’t need to do business with her inner Karen. Such is the world we live in, and the world we are raising our daughters in too.

When our first two children came out female and blonde headed, our circle of anti-colonialist, anti-racist, anti-Karen work expanded. “Privilege” in the village takes on specific form, so we started with the basics: you’re not as special as people think you are. We taught them that when they are given free stuff in stores, they don’t deserve it and it must be shared equally with their friends. When an adult takes something out of their child’s hand to give it to the white girls, our kids are obligated to hand it back to the original child. When an adult is displaced in order to put their white butt in a seat, the girls must decline and sit on the floor. These are some of the house rules on par with “chew with your mouth closed” and “say please and thank you.”

They aren’t perfect. We still have to interrupt their play time to coach them towards kindness. Nine times out of ten they don’t even realize what’s happening when others defer to them. I don’t think your friend is feeling loved, we reflect out loud. Oh, they say, and make a change. The relationship practice gives meaning to the rules. Our goal is to instill habits and attitudes that will support healthy relationships for the long haul. If the rules don’t play out on the playground, they won’t play out in adulthood. There are plenty of right thinking, poorly behaving adults in America right now who know the good they ought to do and are not doing it because theory never became practice. The exercise of relationship hasn’t taken place.

This is the essence of the Karens who are championing All Lives Matter. They are operating out of a philosophical framework in which “liberty and justice for all” is scrawled across the placards of their lives but for some reason, saying Black Lives Matter strikes a chord. Why? My observation, as I hear their arguments on social media, is that their response is entirely cerebral. I’m not hearing any empathy or connection, and as proof of the absence of relationship bubbles to the top like sulfur, I think about my own girls again.

A few months ago, we were reading for homeschool about Vasco de Gama’s voyages around the horn of Africa during which the slave trade expanded greatly. As I read about Africans being tied up and shipped off as slaves, I could feel the wave of emotion rising in my 8-year-old sitting next to me. As I read on, her gaze lowered, and her brow furrowed. Her fists clenched and she stiffened her whole body until she cut me off with a guttural roar. I stopped reading, knowing that my girl and her big feels was going to need a moment to work through this one. I know her heart and had seen it coming. She sputtered for a moment, the rage flooding faster than her brain could find words for and finally she screamed at de Gama and his crew, “THAT WAS TIMO!!!” (her best friend) “Those are my people! Those are my friends!” And her face fell into her hands and her body flopped on my lap and we sobbed together for a long, long time.

Day to day life for our very white daughters involves constant interaction with people who do not look like them. Their friends are exclusively black. The people they admire are exclusively black. The sources of their greatest joys and most favorite memories are all black. While America is at war with itself over its ingrained fear of black men, our two little white girls are absolutely enamored with a whole community of black men who are not only trusted, but also adored. Through repeated exposure, their brains have been wired to perceive black men as protectors and not threats. So while Karen is calling the police because she’s six feet away from a black man minding his own business, our girls are running straight into the arms of black men whom they love. The idea of black people – their friends – being mistreated is intolerable. And it’s not because our girls are better people, or we’re better parents – it’s simply because they’ve had the right kinds of experience.

That day, as we read about the start of the slave trade, my daughter got her first taste of dehumanization. By entering into the gallows of the slave ship, she felt helpless and betrayed by her own skinfolk, overwhelmed by 500 years of evil that she couldn’t undo and didn’t know how to make right. I wasn’t going to talk her out of her grief. I’m glad she felt it. The ability to lament deeply the wrongs of people who look like us is a necessary part of growing up un-Karen.

I’ve been watching the dumpster fire of social media interaction the last few weeks as black folks are BEGGING to be heard and white America is doing a barely mediocre job of listening. The BLM allies are growing increasingly frustrated because they are working overtime in the education department – trying to drop knowledge on every single Karen who is crying taupe tears because her soul is wounded by the idea that anyone else’s life should matter too. I see it. The precious few woke white women are on the verge of hysterics wondering why Karen just doesn’t get it. And of course, Brad, Chad, Brenda and Becky are showing up to add their piece too and the air smells rancid like white supremacy. The riots are visible symbols of invisible pain and moment by moment it's ambiguous whether this is moving forward or backward.

But none of this should be surprising. Ultimately, America needs to experience healing, and that will never happen if people are not in relationship. What separates the Karens from the people trying to rein them in is that the white people who “get it” all have significant relationships within the black community.

I’m not talking about “token black friends,” I mean these bridge builders are IN COMMUNITY with people who don’t look like them. They spend considerable time in each other’s homes. Their children are best friends. They share values and a vision for their neighborhood. They break bread. They like each other. They love each other. And the depth of the relational bond is significant enough that when one hurts, the other hurts. Of course their black friends’ lives matter. And it is for these white folks that “dismantling systemic racism” is not an intellectual exercise – it's personal.

Right now, I’m seeing a lot of resources circling about books to read and conversations to have and that’s awesome, but it isn’t relational enough. Studying black history is essential, but distantly academic. Karens aren’t dumb, they are disconnected – from black pain, from the consequences of their privilege, from reality. I’m pretty sure Karens have google. What they don’t have are black friends. Even if it’s in their heads, it’s not in their hearts, and it’s not in their hearts, because it’s not in their homes. The bridge between knowledge and action is the motivation to care, and that only comes from meaningful relationship.

Last night Bronwyn was curled up on the couch reading the children’s book Beatrice’s Goat about a little girl in Africa whose family receives a goat from an NGO. Reaching the end, she hopped off the couch and said, “Hey, it says Beatrice lives in a small African village! Do you know where we can find a small African village?” Jeremy and I just looked at each other, and then at her and we both laughed, “Bronwyn, you literally live in a small African village. We literally run a program to manage livestock for 300 families just like Beatrice…” And she just looked at us and was like, Oh. I guess you’re right! Despite the fact that this book was describing the backdrop of her life, it was a story to her and therefore looked new and unfamiliar. Beatrice’s life wasn’t something she was living, it was something she was reading. Text is… textual. But her friends whom she throws her arms around and feels in the flesh – that’s what’s real.

Children need black hands to shake and hi-five and hold. They need black friends, black teachers, black doctors, and black pastors to admire. Our black son needs to see faces who look like him and our white girls need to see faces who don’t. The key to breaking the Karen cycle is to provide our girls with repeated experiences of sustained, positive interaction with black people – in particular black men – over the course of their growing up years. I don’t believe there is any substitute for this.

I can hear Karen’s brain processing: Not all of us live in Africa, Bethany. Finding this in the middle of Whitesville, USA is hard. There aren’t many black people here.

Good observation Karen! Fostering meaningful relationships might mean changing schools, or changing churches, changing doctor’s offices or neighborhoods or even towns.

We know families who have uprooted themselves in search of diversity, and I applaud them for that. It may sound radical, but I wouldn’t even be throwing it out for consideration if I wasn’t 110% convinced that it’s worth it. Racial reconciliation requires relationship. Full stop.

I appreciate that not every family is in a position to actually MOVE, so it does beg the question, how far should the pursuit of racial diversity go? That’s up to you – how much do you want your heart to grow?

Our family would be willing to go pretty darn far. Because we know from experience that it’s not a sacrifice. It’s a gift. To us, and to the Karens who need someone to bear witness to uncommon love.